Activated charcoal: how does it relieve intestinal gas?

Used for thousands of years, activated charcoal is reputed to be the most effective natural remedy for reducing gas. Discover precisely how this substance works to combat bloating and flatulence.

Recap: what causes intestinal gas?

Production of intestinal gas is a normal process that affects everyone. It is primarily caused by the accumulation of ingested air in the gut (mostly taken in when we eat), as well as by the fermentation by gut bacteria of certain non- or low-digestible carbohydrates (such as FODMAPs) (1-2). The resulting gas is then released in the form of flatulence: healthy males, for example, pass wind around 14 times a day on average, mainly after meals (3).

Some people, however, suffer from excessive flatulence. This is normally the result of over-fermentation, abnormally long retention of air in the intestinal tract, or the presence of certain bacteria in the gut flora. Occasionally, it can be caused by malabsorption or a food intolerance.

Though harmless in itself, flatulence is often synonymous with social embarrassment and digestive discomfort. It is sometimes accompanied by bloating, abdominal distension or pressure, loud gurgling (or borborygmi to use the medical term), and even pain in the navel and lower abdomen areas (5).

What exactly is activated charcoal?

Also known as activated carbon, activated charcoal is made from a carbon-rich raw material. This can be either animal-source (bone) or plant-source (wood, coconut shells …)

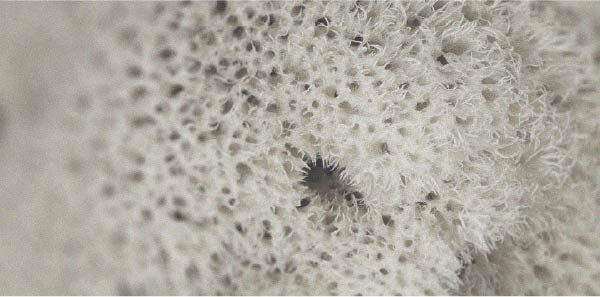

Unlike the charcoal we use for barbecues, activated charcoal undergoes various treatments which profoundly change its structure. The aim is to increase its surface area and make it more porous.

With lots of small holes in its sponge-like surface, activated charcoal easily captures and retains a whole host of undesirable compounds: this is known as adsorption. As our ancient forebears guessed, it is this property – exploited by Hippocrates himself – which is responsible for its many therapeutic applications, particularly in the areas of decontamination and detoxification (6-7).

This structural transformation takes place in two stages:

- carbonization: here, the carbon is charred at very high temperatures (600°C-900°C) to eliminate impurities and ensure only the charcoaled matrix remains. The initial ‘dimples’, the pores, become wider;

- activation: whether physical (thermal shock) or chemical (use of acids), activation unblocks the pores by removing tar to further increase its adsorbent capacity.

Activated charcoal and flatulence: how does it work?

It’s now recognized that activated charcoal helps to reduce excessive post-prandial flatulence (8). So by extension, it also has a beneficial effect on associated bloating, by relieving the abdominal area of this ‘weight of air’. But how does it actually do this?

Once ingested, activated charcoal reaches the gut intact: it is neither denatured nor altered by digestion (9).

It’s at this point that its adsorption properties come into play. With a negative electrical charge, its outer surface attracts positively-charged particles – including gases and certain toxins – trapping them in its pores. Like a magnet, but on a microscopic scale!

Though it’s tempting to use the sponge metaphor, it’s not strictly accurate. The substances captured do not get through to the heart of the charcoaled structure (unlike water which seeps into the foam of a sponge). They remain on the surface, settling in the cavities created by the activation – like a key entering a lock.

Though neutralized, the adsorbed compounds are not physically destroyed: they complete their journey anchored to the charcoal, right up to the end of the digestive tract, where they are then excreted via stools.

What is the link between activated charcoal and gut flora?

Although the mechanisms responsible require further clarification, activated charcoal may, by trapping certain waste-products in its net, have a direct effect on gut microbiota composition. Scientists are currently investigating its use as an adjuvant to those antibiotics likely to disrupt the balance of bacterial flora (10).

And it seems that an unstable flora with little diversity may be associated with lower tolerance to intestinal gases (11).

Which activated charcoal supplement should you choose?

Depending on the activation process used, activated charcoal has varying degrees of porosity which determines the type of molecule adsorbed. Trapping gases requires very narrow pores (sometimes less than a nanometer) (12).

And the quality of the raw material used influences the number and size of pores obtained (13).

It’s best, then, to opt for a plant-source activated charcoal with a sufficiently granular micropore network, which will ensure more effective adsorption of intestinal gases (the supplement Charcoal, obtained from a resinous wood, is activated to produce ultra-fine porosity).

References

- Magge S, Lembo A. Low-FODMAP Diet for Treatment of Irritable Bowel Syndrome. Gastroenterol Hepatol (N Y). 2012 Nov;8(11):739-45. PMID: 24672410; PMCID: PMC3966170.

- Cormier RE. Gaz abdominal. Dans : Walker HK, Hall WD, Hurst JW, éditeurs. Méthodes cliniques : l'histoire, les examens physiques et de laboratoire. 3ème édition. Boston : Butterworths ; 1990. Chapitre 90. Disponible sur : https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK417/

- Hasler WL. Gas and Bloating. Gastroenterol Hepatol (N Y). 2006 Sep;2(9):654-662. PMID: 28316536; PMCID: PMC5350578.

- Deng Y, Misselwitz B, Dai N, Fox M. Lactose Intolerance in Adults: Biological Mechanism and Dietary Management. 2015 Sep 18;7(9):8020-35. doi: 10.3390/nu7095380. PMID: 26393648; PMCID: PMC4586575.

- Zhang L, Sizar O, Higginbotham K. Meteorism. [Updated 2021 Oct 21]. In: StatPearls [Internet]. Treasure Island (FL): StatPearls Publishing; 2022 Jan-. Available from: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK430851/

- Zellner T, Prasa D, Färber E, Hoffmann-Walbeck P, Genser D, Eyer F. The Use of Activated Charcoal to Treat Intoxications. Dtsch Arztebl Int. 2019 May 3;116(18):311-317. doi: 10.3238/arztebl.2019.0311. PMID: 31219028; PMCID: PMC6620762.

- Neuvonen PJ, Olkkola KT. Oral activated charcoal in the treatment of intoxications. Role of single and repeated doses. Med Toxicol Adverse Drug Exp. 1988 Jan-Dec;3(1):33-58. doi: 10.1007/BF03259930. PMID: 3285126.

- Hall RG Jr, Thompson H, Strother A. Effects of orally administered activated charcoal on intestinal gas. Am J Gastroenterol. 1981 Mar;75(3):192-6. PMID: 7015846.

- Silberman J, Galuska MA, Taylor A. Charbon activé. [Mise à jour le 5 juillet 2022]. Dans : StatPearls [Internet]. Treasure Island (FL): StatPearls Publishing; 2022 janvier-. Disponible sur : https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK482294/

- Yuzuriha K, Yakabe K, Nagai H, Li S, Zendo T, Zai K, Kishimura A, Hase K, Kim YG, Mori T, Katayama Y. Protection of gut microbiome from antibiotics: development of a vanco.-specific adsorbent with high adsorption capacity. Biosci Microbiota Food Health. 2020;39(3):128-136. doi: 10.12938/bmfh.2020-002. Epub 2020 Feb 29. PMID: 32775131; PMCID: PMC7392918.

- Manichanh C, Eck A, Varela E, Roca J, Clemente JC, González A, Knights D, Knight R, Estrella S, Hernandez C, Guyonnet D, Accarino A, Santos J, Malagelada JR, Guarner F, Azpiroz F. Anal gas evacuation and colonic microbiota in patients with flatulence: effect of diet. 2014 Mar;63(3):401-8. doi: 10.1136/gutjnl-2012-303013. Epub 2013 Jun 13. PMID: 23766444; PMCID: PMC3933177.

- Li L, Sun F, Gao J, Wang L, Pi X, Zhao G. Broadening the pore size of coal-based activated carbon via a washing-free chem-physical activation method for high-capacity dye adsorption. RSC Adv. 2018 Apr 18;8(26):14488-14499. doi: 10.1039/c8ra02127a. PMID: 35540785; PMCID: PMC9079918.

Keywords

176 Days

EXCELENTE TODO

EXCELENTE EN SERVICIO Y PRODUCTOS LOS RECOMIENDO¡¡ GRACIAS¡¡

ANTONIO ARRIAGA

176 Days

EXCELENTE TODO

EXCELENTE EN SERVICIO Y PRODUCTOS LOS RECOMIENDO¡¡ GRACIAS¡¡

ANTONIO ARRIAGA

176 Days

EXCELENTE TODO

EXCELENTE EN SERVICIO Y PRODUCTOS LOS RECOMIENDO¡¡ GRACIAS¡¡

ANTONIO ARRIAGA

371 Days

Productos de excelente calidad!

Productos de excelente calidad!

CRUZ Francisco

371 Days

Productos de excelente calidad!

Productos de excelente calidad!

CRUZ Francisco

371 Days

Productos de excelente calidad!

Productos de excelente calidad!

CRUZ Francisco

460 Days

Suplementos de calidad

Me encantan los probioticos de esta empresa empeze a leer el libro "el revolucionario mundo de los probioticos" Esta empresa tiene todos los probioticos que este libro menciona en ningun lugar los eh podido encontrar solo en Super Smart Los resultados que hemos obtenido en nuestra salud con los probioticos que solo se encuentran en esta empresa an sido sorprendentes. Muy muy agradecida con Super Smart . Si tuvira mil estrellas se las daría.

Cliente

460 Days

Suplementos de calidad

Me encantan los probioticos de esta empresa empeze a leer el libro "el revolucionario mundo de los probioticos" Esta empresa tiene todos los probioticos que este libro menciona en ningun lugar los eh podido encontrar solo en Super Smart Los resultados que hemos obtenido en nuestra salud con los probioticos que solo se encuentran en esta empresa an sido sorprendentes. Muy muy agradecida con Super Smart . Si tuvira mil estrellas se las daría.

Cliente

460 Days

Suplementos de calidad

Me encantan los probioticos de esta empresa empeze a leer el libro "el revolucionario mundo de los probioticos" Esta empresa tiene todos los probioticos que este libro menciona en ningun lugar los eh podido encontrar solo en Super Smart Los resultados que hemos obtenido en nuestra salud con los probioticos que solo se encuentran en esta empresa an sido sorprendentes. Muy muy agradecida con Super Smart . Si tuvira mil estrellas se las daría.

Cliente

486 Days

High quality vitamins!

High quality vitamins!

François-Xavier Yang-Ting

580 Days

Siempre muy conforme

Siempre muy conforme

VINAS Marta Noemi

580 Days

Siempre muy conforme

Siempre muy conforme

VINAS Marta Noemi

580 Days

Siempre muy conforme

Siempre muy conforme

VINAS Marta Noemi

912 Days

Productos excelentes

Productos excelentes Entrega a tiempo

VINAS Marta Noemi

912 Days

Productos excelentes

Productos excelentes Entrega a tiempo

VINAS Marta Noemi