10 natural and powerful anti-inflammatories

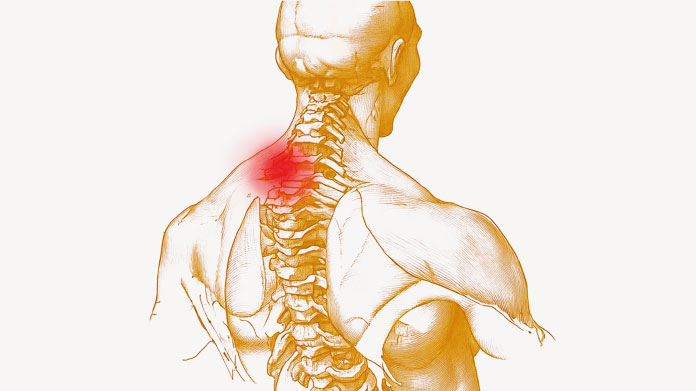

Muscle pain, sciatica, tendonitis … Whether acute or chronic, inflammation can be very painful. Here are 10 tried-and-tested natural anti-inflammatories.

Reminder: what exactly is inflammation?

Inflammation is a natural process, triggered by the body’s immune system in response to an attack (viruses, bacteria, allergens, injuries…), to repair damaged tissue or eliminate potential pathogens (1).

In its acute phase, it manifests in various symptoms such as redness, swelling or localized pain. Often silent and thus more insidious, chronic inflammation persists over time: it is associated with many disorders, such as metabolic and auto-immune diseases, as well as rheumatic conditions (like osteoarthritis) (2).

Alongside prioritizing certain foods in your diet (red berries, broccoli, oily fish …) and controlling your stress levels (3), natural solutions are available that can help boost your resistance to inflammation.

Ginger, a natural anti-inflammatory studied in osteoarthritis

Several studies have demonstrated the benefits and safety of ginger (Zingiber officinale) in individuals suffering from rheumatism and osteoarthritis problems (4). Subjects have reported reduced pain, swelling, and functional impairment in daily activities.

Documented since the 1970s, its ability to inhibit the production of various inflammatory mediators, including leukotrienes and prostaglandins, is thought to be responsible for its anti-inflammatory effect (5). More recently, researchers also appear to have detected an ability to block the expression of certain genes involved in inflammatory processes including those encoding the COX-2 enzyme (6).

Ginger can be used in cooking, but it is also available in a more concentrated form in dietary supplements (such as in Super Gingerols, a ginger extract standardized to 20% gingerols).

Blackcurrant, a regulator of skin and respiratory inflammation

Blackcurrant leaves (Ribes nigrum) constitute another natural anti-inflammatory. Scientists believe their effects come from their flavonols which appear to interfere with IFN-γ signaling , on which the immune response and regulation of inflammation depend. The potential of blackcurrant leaves in easing skin and respiratory conditions is currently being explored (7).

White willow, aspirin’s ancestor

Medicinal use of white willow bark is by no means recent. It dates back to 500 BC when it was used by the Chinese for reducing fever and relieving pain (8). It contains salicin, metabolized in the body into salicylic acid, which makes it the precursor of today’s aspirin (one of the class of non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs).

It has now been introduced into certain supplements (such as Willow Bark Extract standardized to 15% salicin).

Meadowsweet, the natural anti-inflammatory for muscles and joints

Meadowsweet (Filipendula ulmaria) also produces salicylic acid in its flowerheads. It is from its other name, ‘spiraea’, that we get the name ‘aspirin’.

Traditionally popular for relieving headaches and muscle and joint pain, this potent analgesic and natural anti-inflammatory has been shown in vitro to inhibit the COX-2 enzyme as well as the NF-κB signaling pathway, the immune response ‘switch’ (9).

Its many phenolic compounds (including flavonoid glycosides), which are not absorbed by the gut, appear to be bio-converted by the intestinal microbiota, potentially maximizing its efficacy.

Turmeric, a recognized anti-inflammatory ingredient

A much-prized root in Ayurvedic medicine, turmeric (Curcuma longa) enjoys remarkable antioxidant and anti-inflammatory properties as a result of its concentration in curcumin, and more generally, curcuminoids. Several studies suggest these compounds bind to Toll-like receptors to regulate inflammation signaling pathways. At a cellular level, they are thought to also reduce pro-inflammatory molecules including interleukins and TNF-α factor (10).

They are, however, poorly absorbed in the gut, so it’s important to choose a supplement that makes up for this (such as Super Curcuma, in which the curcuminoids are combined with natural phosphatidylcholine to produce a level of absorption 29 times higher than other such supplements on the market) (11).

Boswellia, an ally for joint health

The resin of Boswellia serrata, also known as ‘Indian Frankincense’, is notable for its boswellic acids which are believed to be responsible for its therapeutic benefits. In particular, Boswellia serrata supports joint health (as shown in a study on arthritic rats) as well as respiratory and gastrointestinal function (12).

AKBA appears to be the most active of these boswellic acids at inhibiting an enzyme called 5-LO, which is involved in the inflammatory cascade (that’s why the highly-absorbable supplement Super Boswellia is standardized to 20% AKBA) (13).

Neem, the natural anti-inflammatory for the skin

Neem, or margosa (Azadirachta indica), has a triple antioxidant, anti-inflammatory and anti-pyretic effect(14). Designated as a ‘cure-all’ in Ayurvedic medicine, it supports, amongst others, the skin’s natural defenses.

More specifically, its purifying and detoxifying properties soothe skin that’s prone to allergic reactions or acne (15). It’s used in powder form for home-made skincare/cosmetics as well as in supplement form (such as Neem Extract, which offers a dose of 500 mg of Azadirachta indica extract per capsule).

Nettle, potential relief for joint inflammation

Though negatively associated with uncomfortable stinging, the common nettle or Urtica dioica (the key ingredient in Nettle Root Extract) has actually been shown to be, amongst others, a first-rate natural anti-inflammatory. Containing malic and caffeic acids, polysaccharides and flavonoids, its leaves inhibit the production of prostaglandins, thromboxane, interleukins IL-2 and IL-1, IFN, and tumor necrosis factor (16).

A number of studies are therefore investigating its effects in the area of acute and chronic rheumatism (17).

Sweet clover, an anti-inflammatory for vascular health

Supporting the vascular and venous systems, sweet clover (Melilotus officinalis) also has an anti-inflammatory effect as a result of its unique combination of coumarin, phenolic acids, flavonoids and saponins (18). More specifically, it helps combat inflammation related to veno-lymphatic disorders (the natural venotonic supplement Lymphatonic is based on a sweet clover extract standardized to 18% coumarin for enhanced efficacy) (19).

Roman chamomile, the digestive relaxant

Rich in flavonoids, Roman chamomile (Chamaemelum nobile) is prized for its digestive and soothing properties, especially for relieving irritation of the gastric mucosa and throat. Studies have focused on its interaction with nitric oxide (NO), which in excess becomes pro-inflammatory (20).

Which is the most effective natural anti-inflammatory?

If you’re looking to fully restore your internal balance, it’s probably best to choose a broad spectrum supplement that combines various compounds for a synergistic effect (the product InflaRelief contains 12, carefully-selected, 100% natural compounds, including 3 patented ingredients, as well as a range of the anti-inflammatory substances mentioned above: turmeric, nettle, ginger…)

SuperSmart ADVICE

References

- Stone WL, Basit H, Burns B. Pathology, Inflammation. [Updated 2022 Nov 14]. In: StatPearls [Internet]. Treasure Island (FL): StatPearls Publishing; 2023 Jan-. Available from: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK534820/

- Pahwa R, Goyal A, Jialal I. Chronic Inflammation. [Updated 2022 Aug 8]. In: StatPearls [Internet]. Treasure Island (FL): StatPearls Publishing; 2023 Jan-. Available from: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK493173/

- Liu YZ, Wang YX, Jiang CL. Inflammation: The Common Pathway of Stress-Related Diseases. Front Hum Neurosci. 2017 Jun 20;11:316. doi: 10.3389/fnhum.2017.00316. PMID: 28676747; PMCID: PMC5476783.

- Bartels EM, Folmer VN, Bliddal H, Altman RD, Juhl C, Tarp S, Zhang W, Christensen R. Efficacy and safety of ginger in osteoarthritis patients: a meta-analysis of randomized placebo-controlled trials. Osteoarthritis Cartilage. 2015 Jan;23(1):13-21. doi: 10.1016/j.joca.2014.09.024. Epub 2014 Oct 7. PMID: 25300574.

- Srivastava KC, Mustafa T. Ginger (Zingiber officinale) in rheumatism and musculoskeletal disorders. Med Hypotheses. 1992 Dec;39(4):342-8. doi: 10.1016/0306-9877(92)90059-l. PMID: 1494322.

- Grzanna R, Lindmark L, Frondoza CG. Ginger--an herbal medicinal product with broad anti-inflammatory actions. J Med Food. 2005 Summer;8(2):125-32. doi: 10.1089/jmf.2005.8.125. PMID: 16117603.

- Magnavacca A, Piazza S, Cammisa A, Fumagalli M, Martinelli G, Giavarini F, Sangiovanni E, Dell'Agli M. Ribes nigrum Leaf Extract Preferentially Inhibits IFN-γ-Mediated Inflammation in HaCaT Keratinocytes. Molecules. 2021 May 20;26(10):3044. doi: 10.3390/molecules26103044. PMID: 34065200; PMCID: PMC8160861.

- Van der Auwera A, Peeters L, Foubert K, Piazza S, Vanden Berghe W, Hermans N, Pieters L. In Vitro Biotransformation and Anti-Inflammatory Activity of Constituents and Metabolites of Filipendula ulmaria. 2023 Apr 20;15(4):1291. doi: 10.3390/pharmaceutics15041291. PMID: 37111776; PMCID: PMC10146082.

- Peng Y, Ao M, Dong B, Jiang Y, Yu L, Chen Z, Hu C, Xu R. Anti-Inflammatory Effects of Curcumin in the Inflammatory Diseases: Status, Limitations and Countermeasures. Drug Des Devel Ther. 2021 Nov 2;15:4503-4525. doi: 10.2147/DDDT.S327378. PMID: 34754179; PMCID: PMC8572027.

- Xie J, Li Y, Song L, Pan Z, Ye S, Hou Z. Design of a novel curcumin-soybean phosphatidylcholine complex-based targeted drug delivery systems. Drug Deliv. 2017 Nov;24(1):707-719. doi: 10.1080/10717544.2017.1303855. PMID: 28436718; PMCID: PMC8241017.

- Siddiqui MZ. Boswellia serrata, a potential antiinflammatory agent: an overview. Indian J Pharm Sci. 2011 May;73(3):255-61. doi: 10.4103/0250-474X.93507. PMID: 22457547; PMCID: PMC3309643.

- Sailer ER, Subramanian LR, Rall B, Hoernlein RF, Ammon HP, Safayhi H. Acetyl-11-keto-beta-boswellic acid (AKBA): structure requirements for binding and 5-lipoxygenase inhibitory activity. Br J Pharmacol. 1996 Feb;117(4):615-8. doi: 10.1111/j.1476-5381.1996.tb15235.x. PMID: 8646405; PMCID: PMC1909340.

- Alzohairy MA. Therapeutics Role of Azadirachta indica (Neem) and Their Active Constituents in Diseases Prevention and Treatment. Evid Based Complement Alternat Med. 2016;2016:7382506. doi: 10.1155/2016/7382506. Epub 2016 Mar 1. PMID: 27034694; PMCID: PMC4791507.

- Rajaiah Yogesh H, Gajjar T, Patel N, Kumawat R. Clinical study to assess efficacy and safety of Purifying Neem Face Wash in prevention and reduction of acne in healthy adults. J Cosmet Dermatol. 2022 Jul;21(7):2849-2858. doi: 10.1111/jocd.14486. Epub 2021 Sep 30. PMID: 34590784.

- Bhusal KK, Magar SK, Thapa R, Lamsal A, Bhandari S, Maharjan R, Shrestha S, Shrestha J. Nutritional and pharmacological importance of stinging nettle (Urtica dioica L.): A review. Heliyon. 2022 Jun 22;8(6):e09717. doi: 10.1016/j.heliyon.2022.e09717. PMID: 35800714; PMCID: PMC9253158.

- Dhouibi R, Affes H, Ben Salem M, Hammami S, Sahnoun Z, Zeghal KM, Ksouda K. Screening of pharmacological uses of Urtica dioica and others benefits. Prog Biophys Mol Biol. 2020 Jan;150:67-77. doi: 10.1016/j.pbiomolbio.2019.05.008. Epub 2019 Jun 1. PMID: 31163183.

- Liu YT, Gong PH, Xiao FQ, Shao S, Zhao DQ, Yan MM, Yang XW. Chemical Constituents and Antioxidant, Anti-Inflammatory and Anti-Tumor Activities of Melilotus officinalis (Linn.) Molecules. 2018 Jan 29;23(2):271. doi: 10.3390/molecules23020271. PMID: 29382154; PMCID: PMC6017420.

- Jasicka-Misiak I, Makowicz E, Stanek N. Polish Yellow Sweet Clover (Melilotus officinalis L.) Honey, Chromatographic Fingerprints, and Chemical Markers. Molecules. 2017 Jan 15;22(1):138. doi: 10.3390/molecules22010138. PMID: 28098847; PMCID: PMC6155788.

- Bhaskaran N, Shukla S, Srivastava JK, Gupta S. Chamomile: an anti-inflammatory agent inhibits inducible nitric oxide synthase expression by blocking RelA/p65 activity. Int J Mol Med. 2010 Dec;26(6):935-40. doi: 10.3892/ijmm_00000545. PMID: 21042790; PMCID: PMC2982259.

Keywords

1 Days

First bottle has been finished

First bottle has been finished. 2 bottles remaining for 3 month time frame trial as recommended

CORCORAN Pamela

6 Days

repeat customer

recommended by my doctor. easy to create an account. Discounts and specials are appreciated. packaging and delivery is dependable. Capsules easy to digest. I've had some some capsules and tablets that are broken inside their bottles.

Kokee

10 Days

Order was shipped on time and packaged…Wonderful Jobs!

Order was shipped on time and packaged excellently.

DMHoge

17 Days

great products and prices

great products and prices

Marie

22 Days

Easy to navigate site

Easy to navigate site, had what I was searching for, good price. easy order-check out

James Tucker

29 Days

My skin is clearing up nicely!

Pretty good for my skin so far.

Christian

31 Days

The new packaging is excellent

The new packaging is excellent - finally! No more squashed boxes and torn envelopes.

GORAN

32 Days

Great Product

Great Product

Larry Garrett

36 Days

Quick shipping

Quick shipping; good price. No issues!

Mary McCarty

37 Days

Thr product is very good and is helping…

Thr product is very good and is helping me on my health. Then is always on time

LUGO Luz

40 Days

Buying was fine

Buying was fine. I had problems with the website not recognizing my login info, and had to call to get it fixed. Other than that, everything was good.

David S. Clark

40 Days

Your super maca and super ginseng are…phenomenal

Your super maca and super ginseng are phenomenal supplements that compliment each other when taking them together. Fantastic feeling of well-being and lots of mid day energy without the crash.

Keith Mason

43 Days

I have had amazing results with every…

I have had amazing results with every supplement I've purchased. I am extremely satisfied with this company

kirstin Torres

43 Days

Fine products

Fine products . They are on the leading edge of online supplements. The only issue -so far-is they sometime run out of subscription items.

Jason Argos

46 Days

The ordering process is very user…

The ordering process is very user friendly and the products always come in a timely manner.

CARTER Rhonda